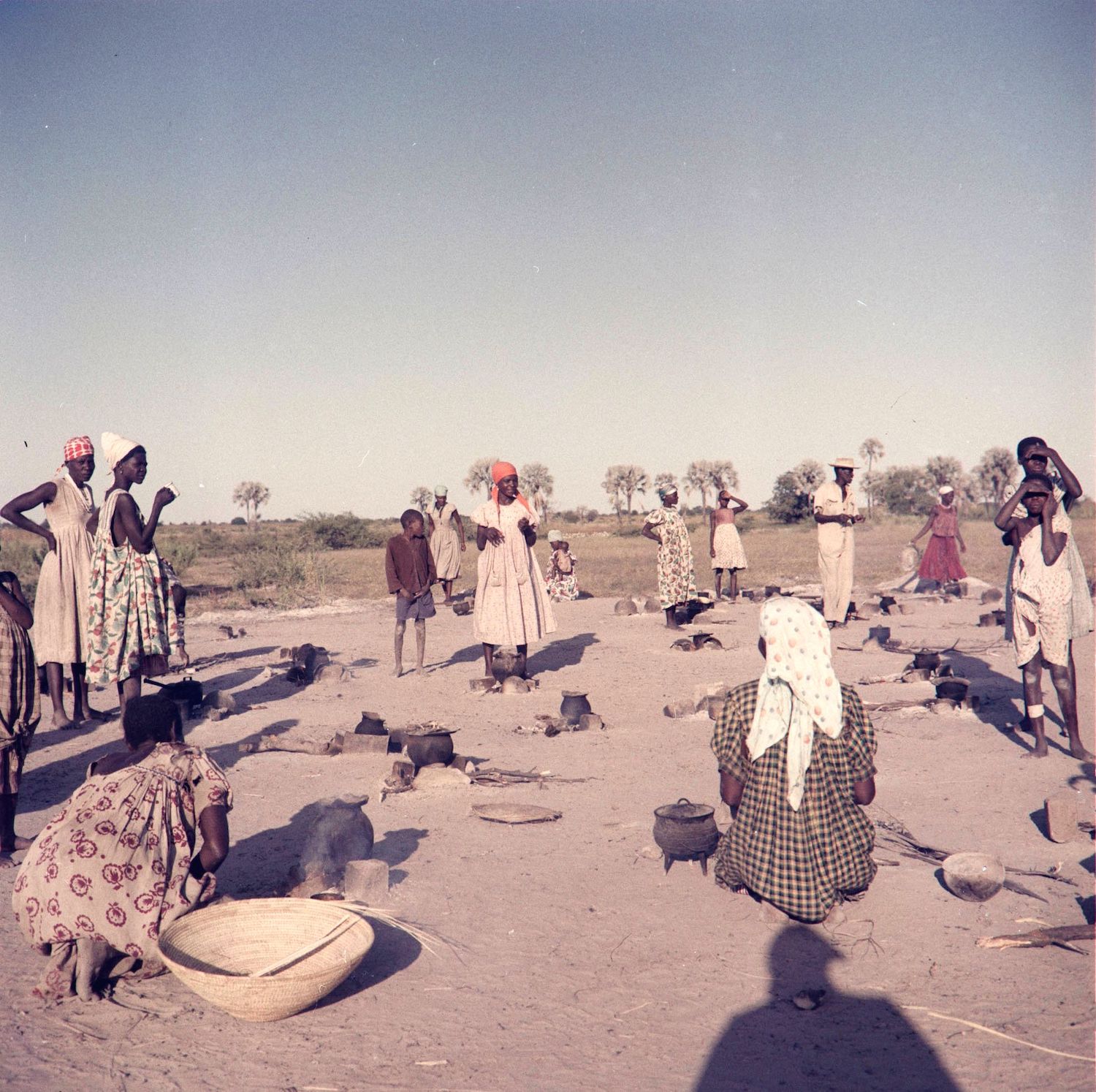

The unseen companion in the archives of photographs is the photographer’s self, a captured shadow. As if they arrested themselves when releasing the shutter, inscribed themselves, if only instinctively, onto the scene of action. Once brought to light, photographs reveal a shady lump in the corner of an image, a blurred silhouette at the edge of the frame or a surreal figure taking the centre stage.

In the images presented here we must often look sideways for the unseen self. At times we need a magnifying glass.

Is the photographer’s shadow a ghost revealing their darker side? Is he a self-loving muse creating or simply accepting—and archiving—a fingerprint if not a composition with himself? Who is the protagonist in these images: the photographer or their shadow? Are these simply snapshots from an extensive and private visual diary with no intention of eliminating or cropping individual images? Or are they carefully crafted visual poems?

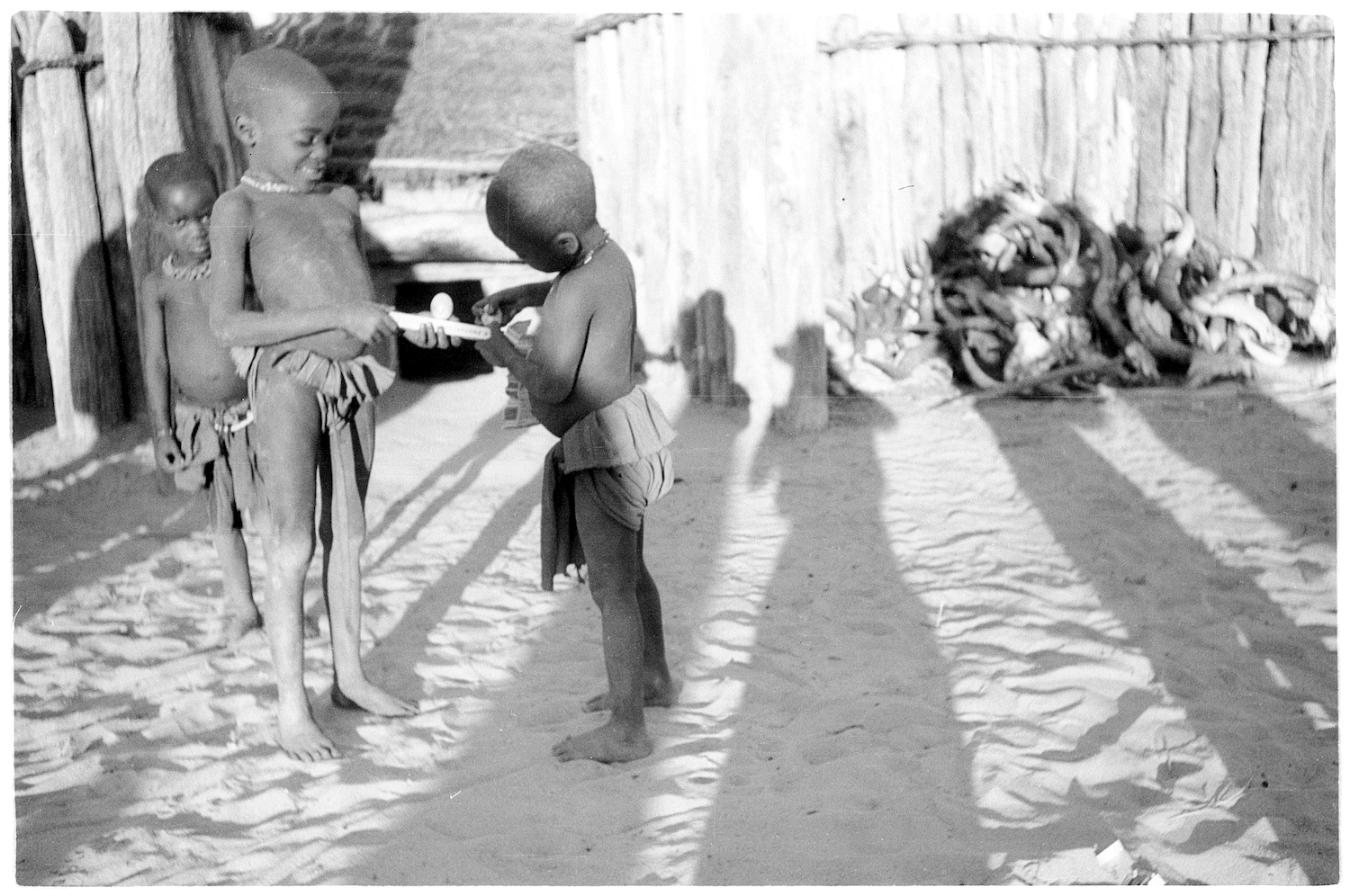

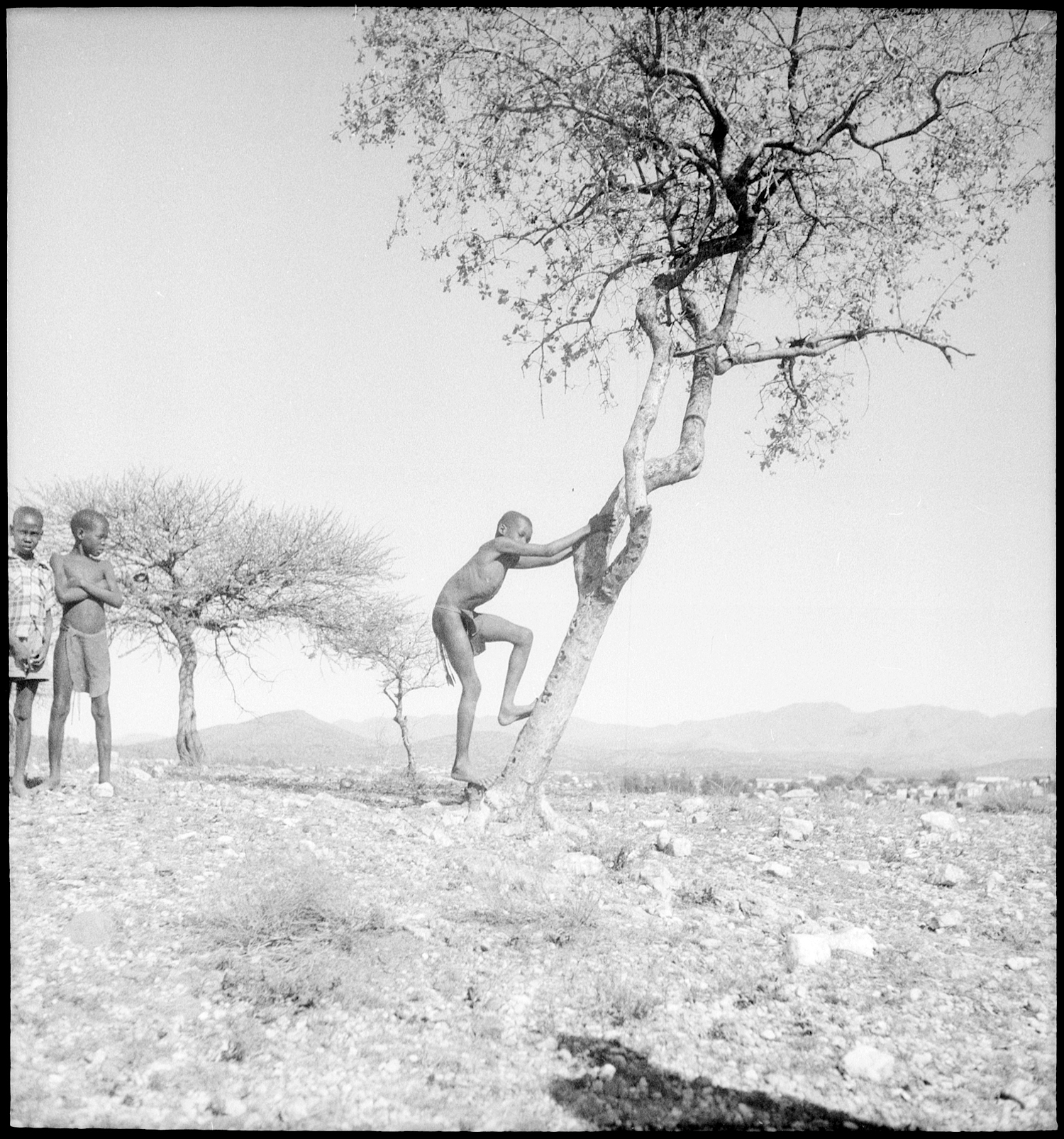

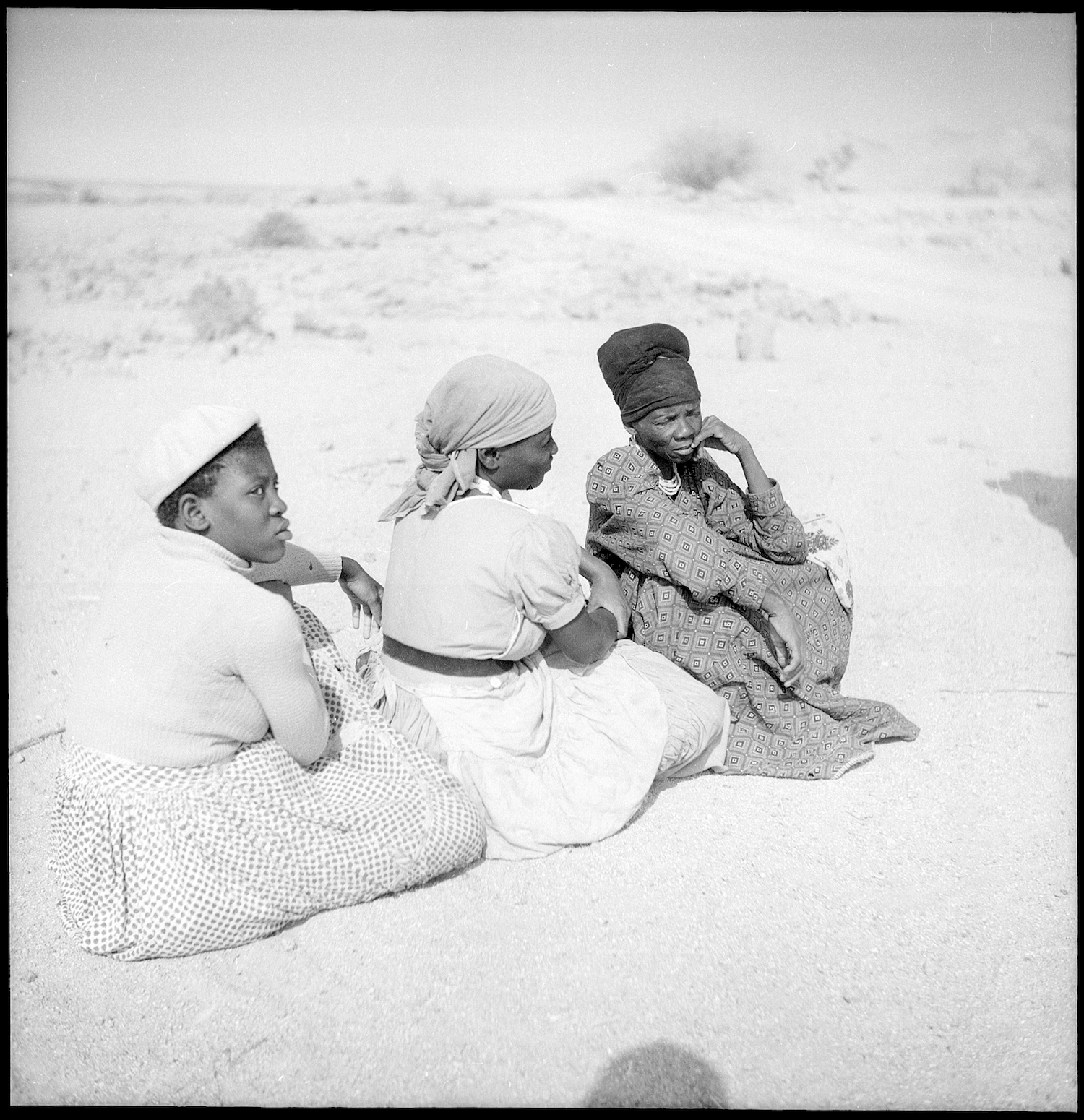

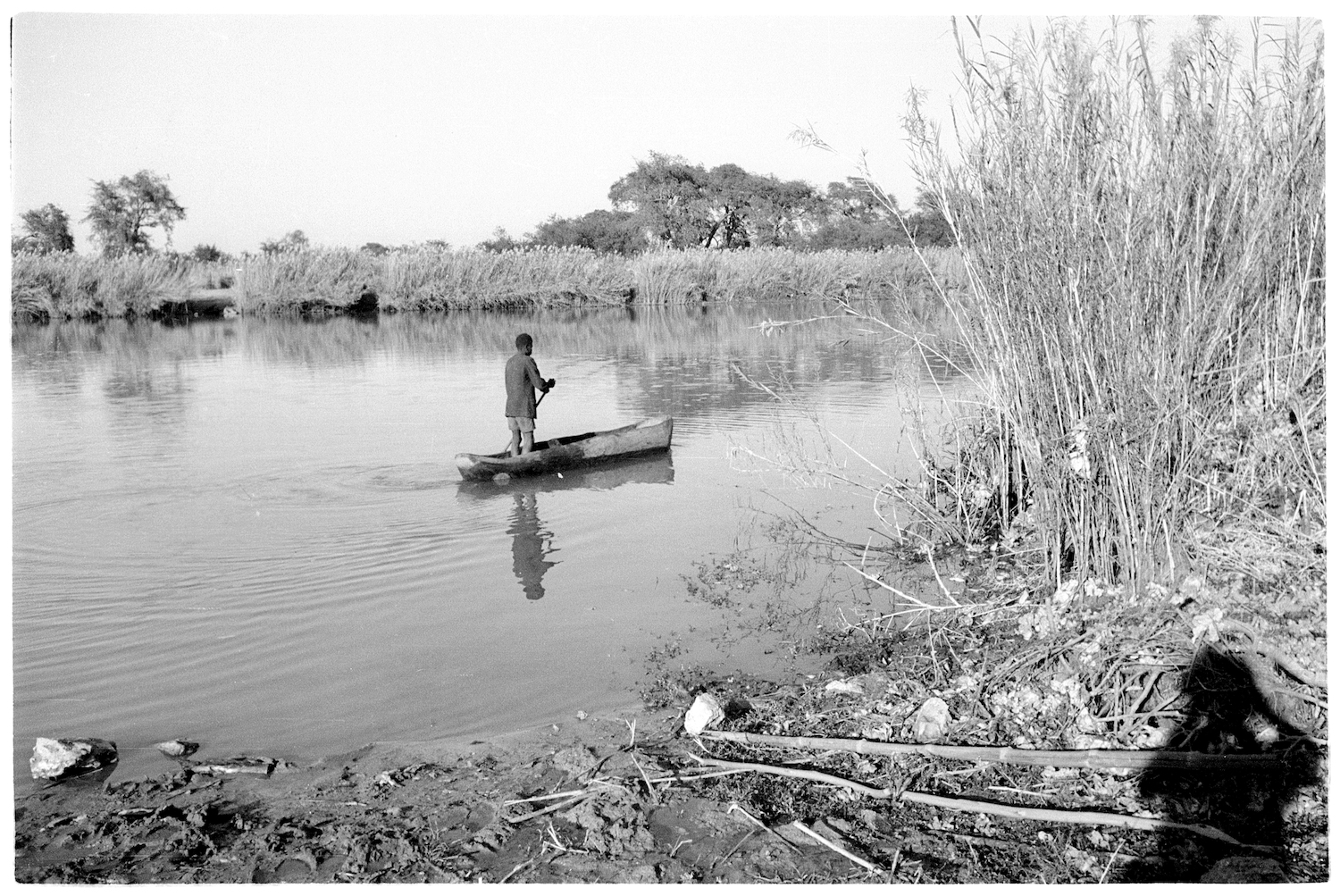

In Bishop Leonard Aula’s spectacles we encounter Ruth Dammann’s piercing reflection as she portrayed him in Oniipa, northern Namibia in 1953. Anneliese Scherz captured, it seems, her own actions and postures as she moved in the 1940s with her Leica or Rollei camera amongst the women and children in northern and central Namibian homesteads, encountered a travel company and river canoeist, or staged a day at the beach. Ilse Steinhoff clearly seems to have encrypted herself as the creator when documenting urban and rural settings in South Africa’s colony.

Is it all about light in sun-drenched Namibia?

Shadow and silhouette photography is usually shot against the source of light. Here, in this series, the inescapable sunlight, usually necessary to objectify the subject, beams from behind the camera and thus also composes—and exposes—the photographer. Whilst the clarity of the subject may have been the principal consideration in the attempts to objectify, the photographer’s shadows enhance their intrusive presence and their active role in producing images. As such they counter any notion of the image as an unmediated and “true” representation of reality and point to photography as process and construction.

And they invite us—archivists, viewers, readers—to reflect on our own positionalities and, indeed, our own shadows when handling and looking at these photographs.

In all of this, power relations reverberate inside and outside the image frames.

Questions abound.

Does the photographer’s shadow reinforces the colonial gaze, frames apartheid subjectivities and enhances colonial aesthetics?

In many images shown here, the shadow confirms the standing position of the photographer and a high angel gaze being cast over and onto the subjects below her and him.

What do we (not) see?

Should we talk about the coloniality of shadows?

Curated by Heidi Brunner, Hemen Heidari, Dag Henrichsen, Susanne Hubler Baier, and Lisa Roulet from the Basler Afrika Bibliographien (BAB) Archives Team. BAB is the largest Namibia documentation centre outside Namibia. Its vast Southern Africa library and archive holdings are mainly used by scholars working on Namibian historical topics with its website providing information ranging from catalogues, books, comics, posters, photographs, and audio-visual recordings from Namibia.