When Dieter Hinrichs from Munich arrived in Windhoek in April 1959 on a two-year contract to work for the well-known photo studio Nitzsche-Reiter on the then Kaiser Street, he was appalled by what he observed:

“Many people are not so sensible, not very receptive towards the fate of others,” he wrote back home in one of his letters. “People are divided into Whites and Blacks and ‘Bastards’ (horrible term, meaning between White and Black) and people seem to be comfortable simply because they are Whites!”

His contract obliged him to cover a wide range of assignments, from advertisements and architectural photography to public events. For the latter, for example, he had to cover the German Carnival, agricultural shows, and horse races in town, or Tintenpalast stagings. Almost always, these activities concerned “white” Windhoek. Other assignments related to studio and darkroom work and, as such, required processing large quantities of film and enlargements for impatient customers.

The team of colleagues at the Nitzsche-Reiter studio reflected the wider social apartheid divisions en miniature: the photographers were all white and regarded as the experts while the assistants were all non-white. Typically, in the archive, the latter’s names only survive as Ewald and Maria. Upon his arrival, proprietor Ottilie Nitzsche-Reiter had instructed Hinrichs not to have any private conversations with the assistants whilst on tour with them and “not letting them walk next to me when we moved around.”

One of them, Hinrichs said, “was a very sympathetic Ovambo, very receptive and helpful and would, no doubt, have become a good photographer.”

Who were Ewald and Maria?

Apparently neither Nitzsche-Reiter nor any other studio trained black Namibians to become professional photographers at the time. “Africans were not allowed to operate commercially,” Hinrichs recalls. The first black Namibian photographers, it seems, were mainly self-taught.

At one stage, Hinrichs engaged in studio photography; his images are published here for the first time.

“I took these when the studio photographer Hannelore Mickan was on holiday. I am not a portrait photographer. But I kept the Rolleiflex negatives.” No names of the couples shown here survive in the archives.

Hinrichs shot his well-known Windhoek Old Location, African dance competition, and forced removal images, which were published in Doek!, Issue 4, in his private capacity and after-hours. Nitzsche-Reiter photographers did, at times, cover events in the Old Location’s Sybill Bowker Hall. In order to do so Hinrichs had an official permit which permitted him to enter the Old Location. He guarded his private photography closely and developed his series on women, men, and children being shuttled in a bus in early 1960 from the Old Location to the newly built and racially segregated Katutura township and to the Windhoek city centre only after his return to Germany.

“Nearly all of my personal photographs were taken with a slight wide-angle (35mm zoom for the Leica camera) as I wanted to be close to the people in order to sense an acceptance of my doings. A sense of rejection, of overstepping a boundary, would have resulted in my retreat. As such I rarely staged a setting and did not use a flash—and during processing the film and concept work I mostly did not crop or frame images.”

He vividly remembers his dislike for an assignment for a public event in Windhoek at which the South African Prime Minister Verwoerd spoke about new apartheid implementation policies.

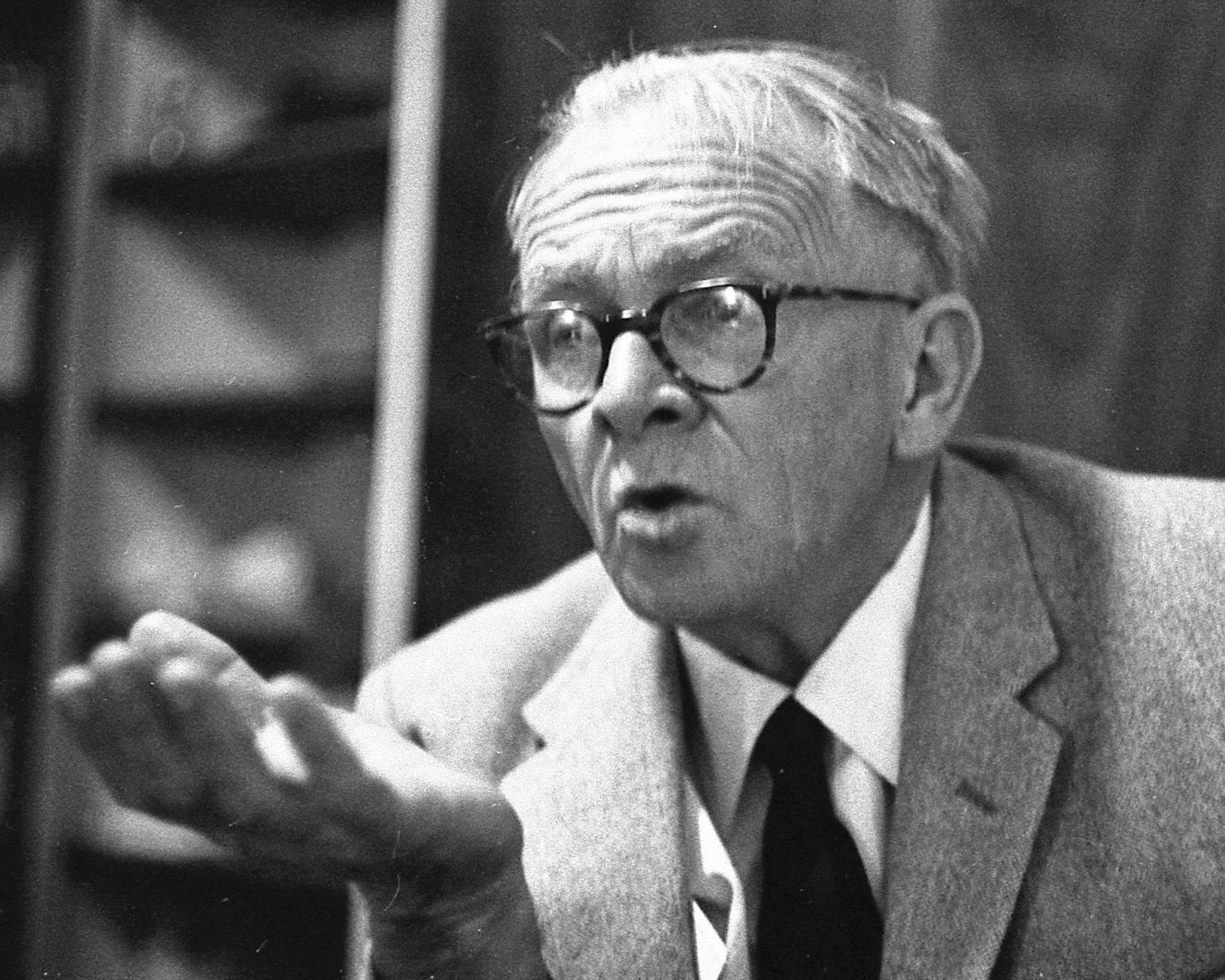

“Much happier was an encounter with the South African writer Alan Paton in Windhoek. I had seen the film Cry, The Beloved Country (1951) based on his novel when I was still in Germany. I could photograph him at a small reception after he had given a reading which was ignored by the local media.”

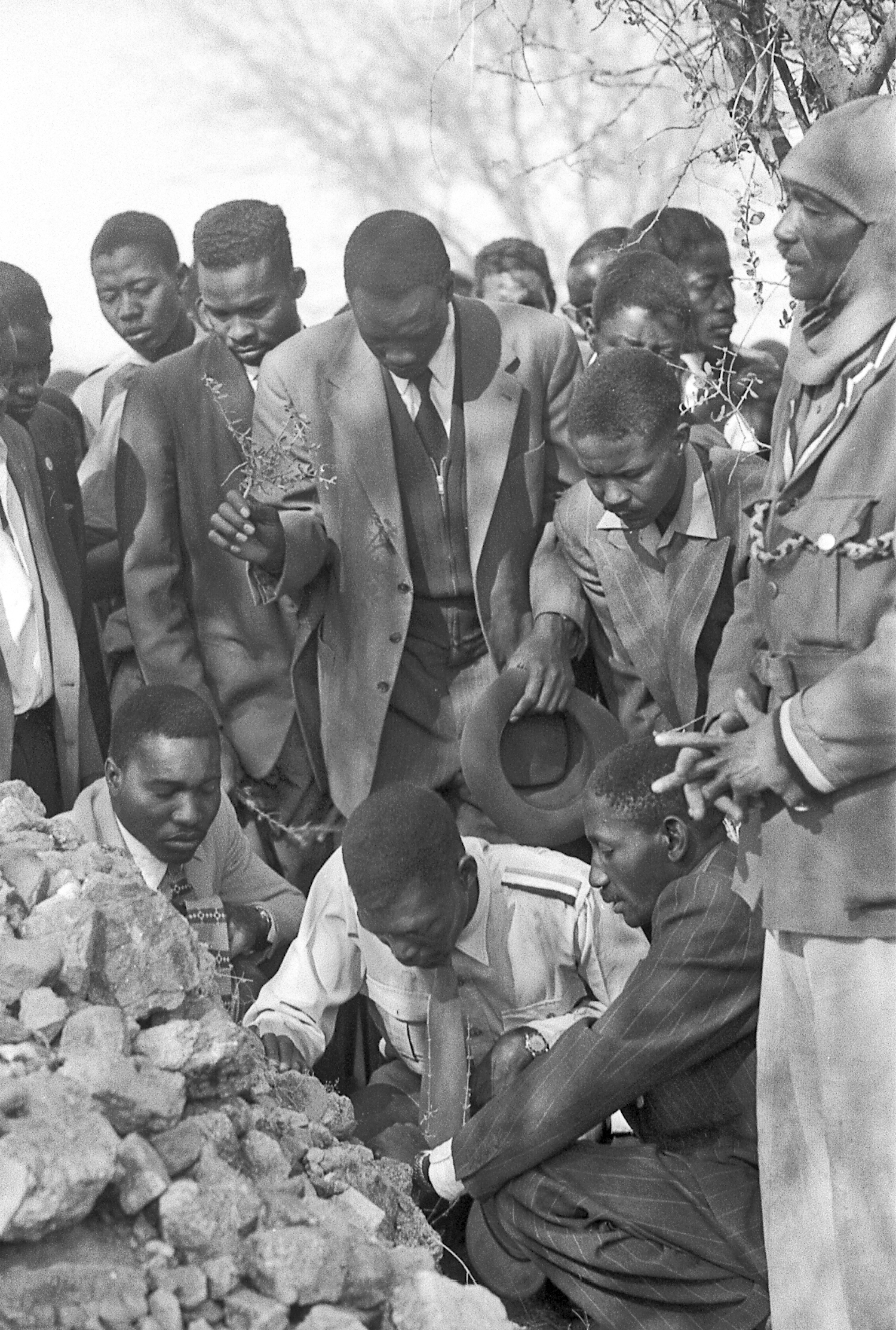

Unbeknown to Hinrichs, the reading had caused a stir amongst Old Location intellectuals when three of them, including Zedekia Ngavirue, were barred by Advocate Hans Joachim Berker from attending. Ngavirue reported the incident in his Old Location newspaper South West News:

“Berker stated to the three interested Africans that he, personally, had no objection to their presence there. But he was sorry … [and] feared that he would be arrested. ‘You know the situation in this country well’, said the advocate. The three Africans could not even be allowed to go into a side-room and listen from there…”.

South West News , short-lived as it was, was the only non-racial newspaper published in Namibia at the time.

Hinrichs cancelled his contract with Nitzsche-Reiter a few months later and left Namibia in December, 1960.

***

This piece is based on exchanges between Dieter Hinrichs (Munich) and Dag Henrichsen (Basler Afrika Bibliographien) and on Hinrichs´archives. His photographs were exhibited at the University of Namibia and the National Archives of Namibia in the mid-1990s and since then appeared in various publications and exhibitions. The encounter with Alan Paton is mentioned in the South West News, No 6, 23 July 1960, retrieved from the open access newspaper edition: https://www.baslerafrika.ch/a-glance-at-our-africa/

Dieter Hinrichs, a German photographer, was born in West Germany in 1932. In 1959 he was engaged by Nitzsche-Reiter, a well-known photography studio in the then South West Africa. During his two-year stay, he moved with his camera beyond the Apartheid divide and documented life in the Old Location and the beginnings of the first families who were forcibly relocated to Katutura in the 1960s. Hinrichs’ photographs have been previously exhibited at the National Archives of Namibia and resonate with the richness and loss of a bygone space and time.

Dag Henrichsen is a Namibian historian at the Basler Afrika Bibliographien (BAB) – Namibia Resource Centre & Southern Africa Library in Switzerland. BAB is the largest Namibia documentation centre outside Namibia. Its vast library and archive holdings are mainly used by scholars working on Namibian historical topics with its website providing information ranging from catalogues, books, comics, posters, photographs, and audio-visual recordings from Namibia.