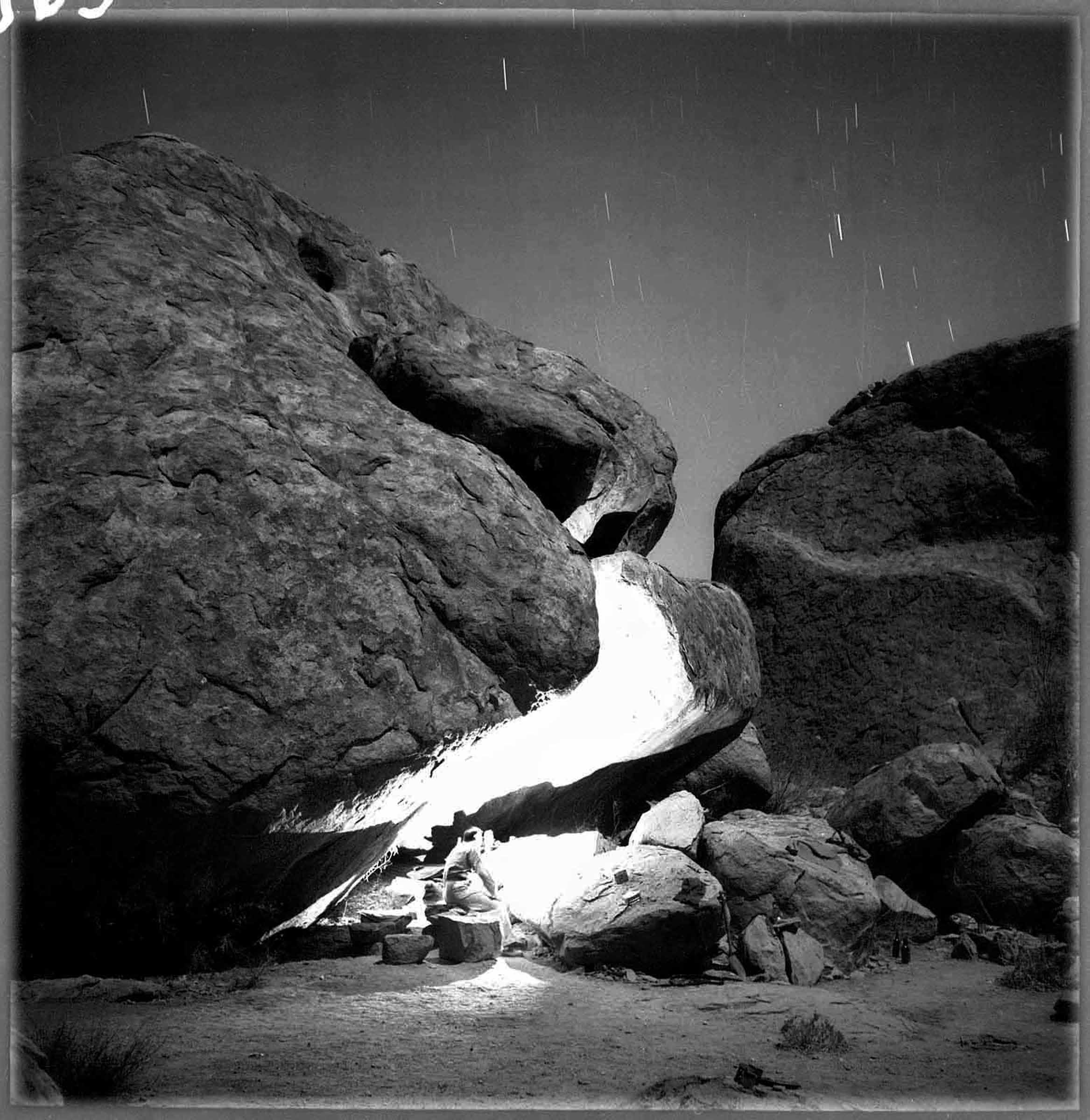

Colonial photography archives construct Whiteness in ever-changing transformations. In this series of negatives from the late 1940s and early 1950s, researchers and photographers engage with Namibia’s rock art, in particular, the so-called “White Lady”, the emblematic rock art figure entangled in an impressive frieze of numerous paintings in the Dâureb (Brandberg Mountain) in the northwestern Erongo Region.

“We called her the ‘White Lady’,” said Mary Boyle who, together with the French pre-historian Abbé Henri Breuil, and photographers Anneliese and Ernst Rudolf Scherz, conducted the first substantial research of the sprawling frieze. Devoid of any considerations of African history, the figure was instantly catapulted into Eurocentric history and scientific interpretations, with Boyle claiming it to resemble a Mediterranean figure from the antique palace of Knossos in Crete.

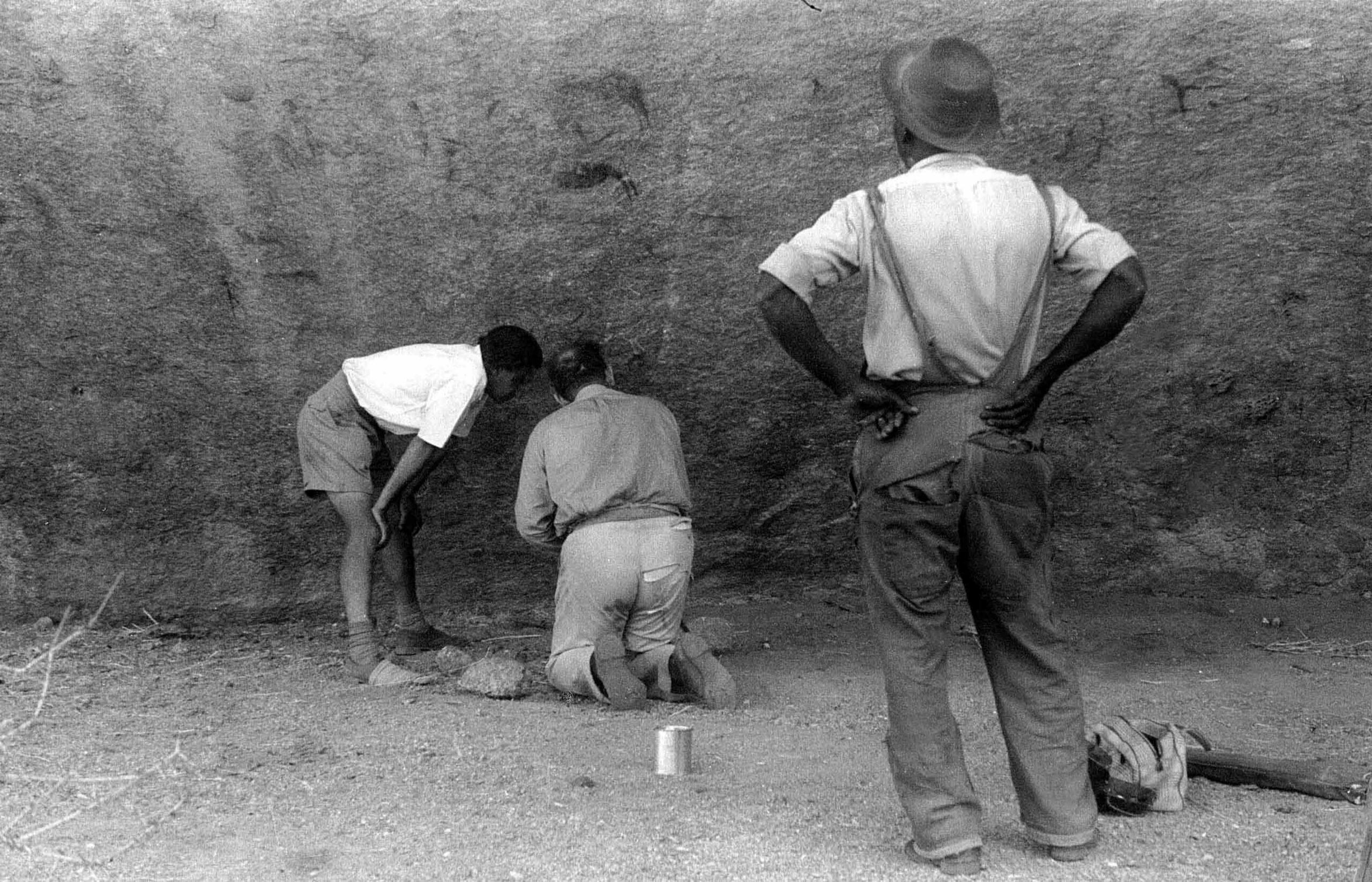

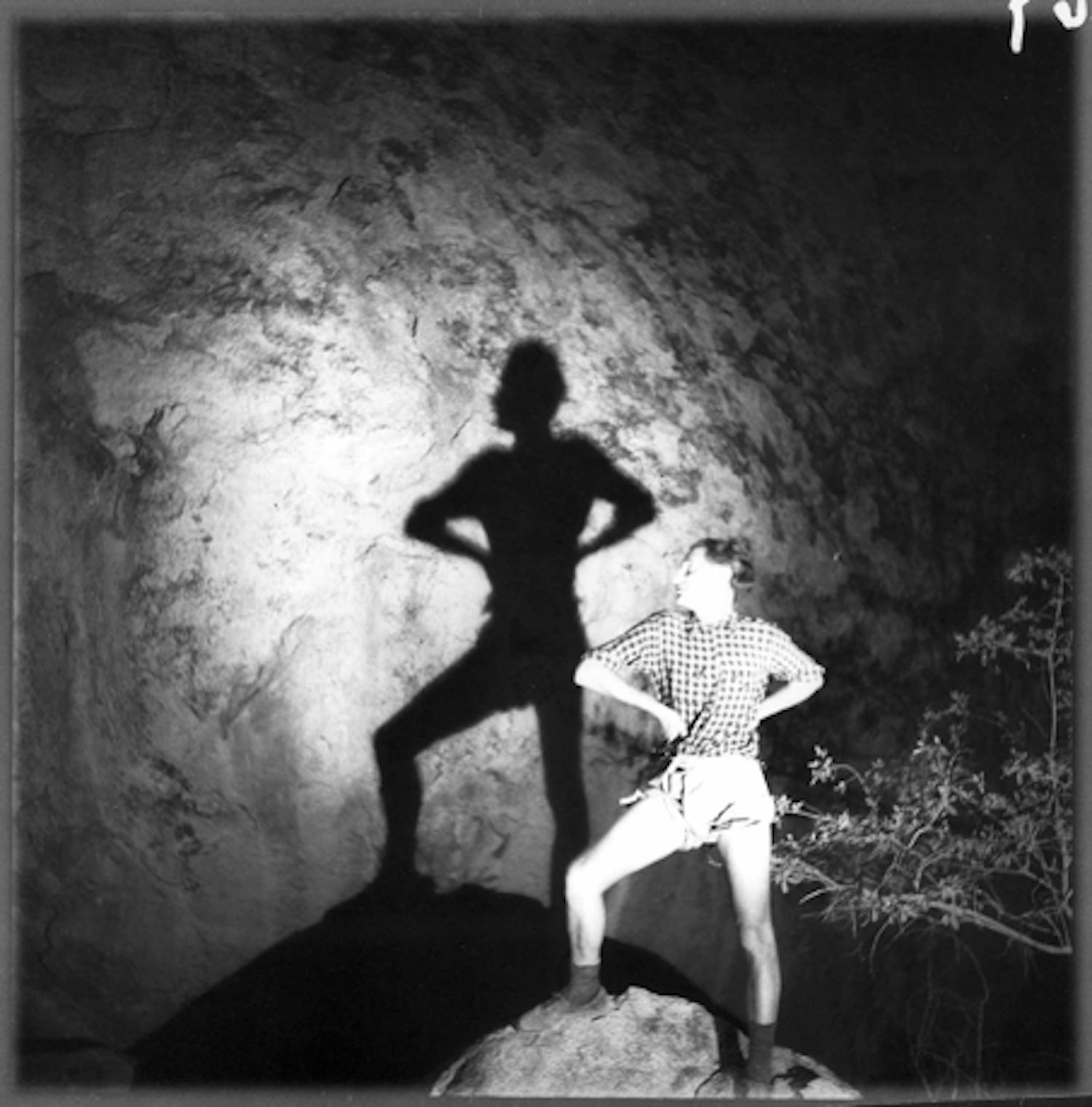

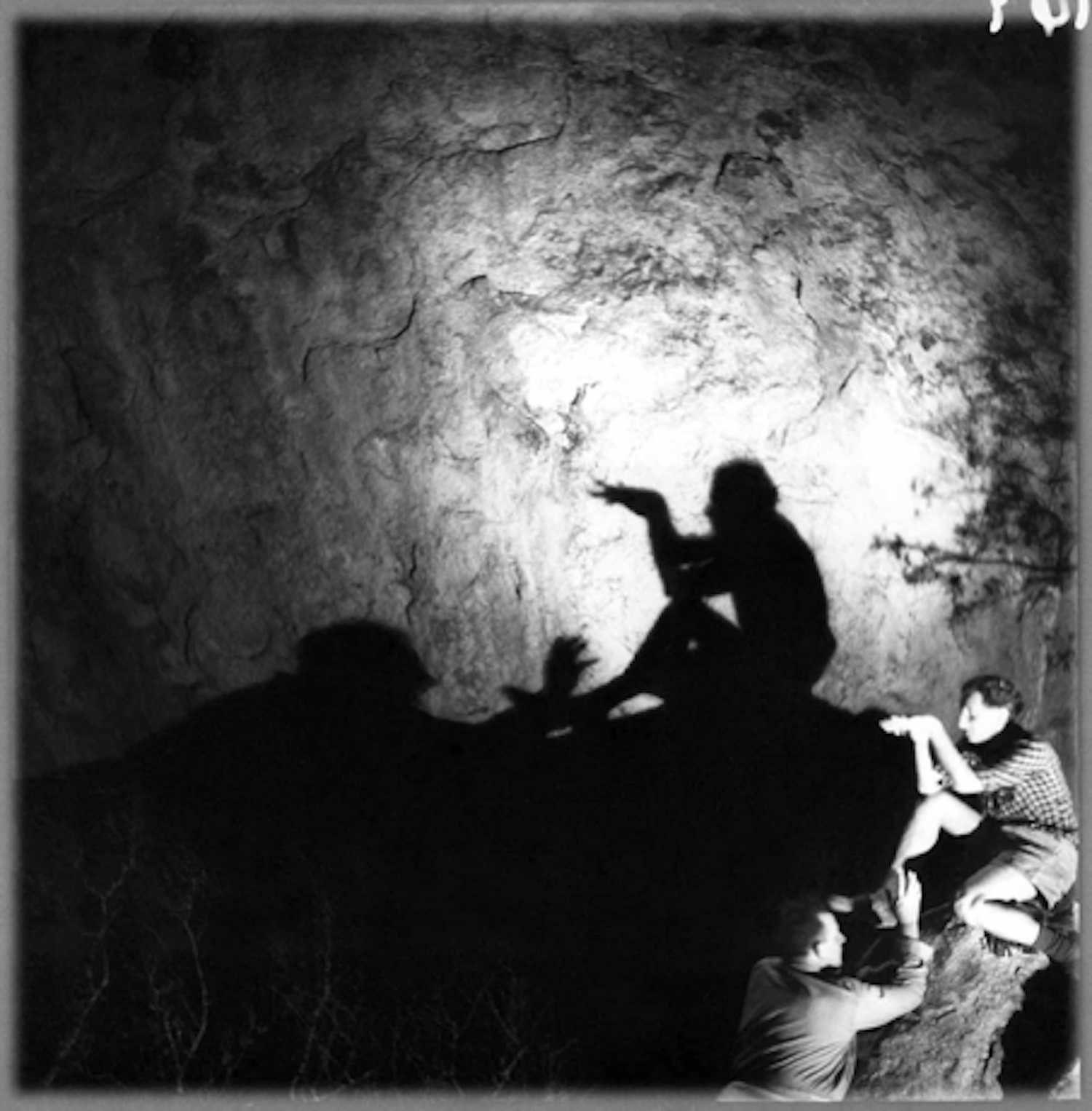

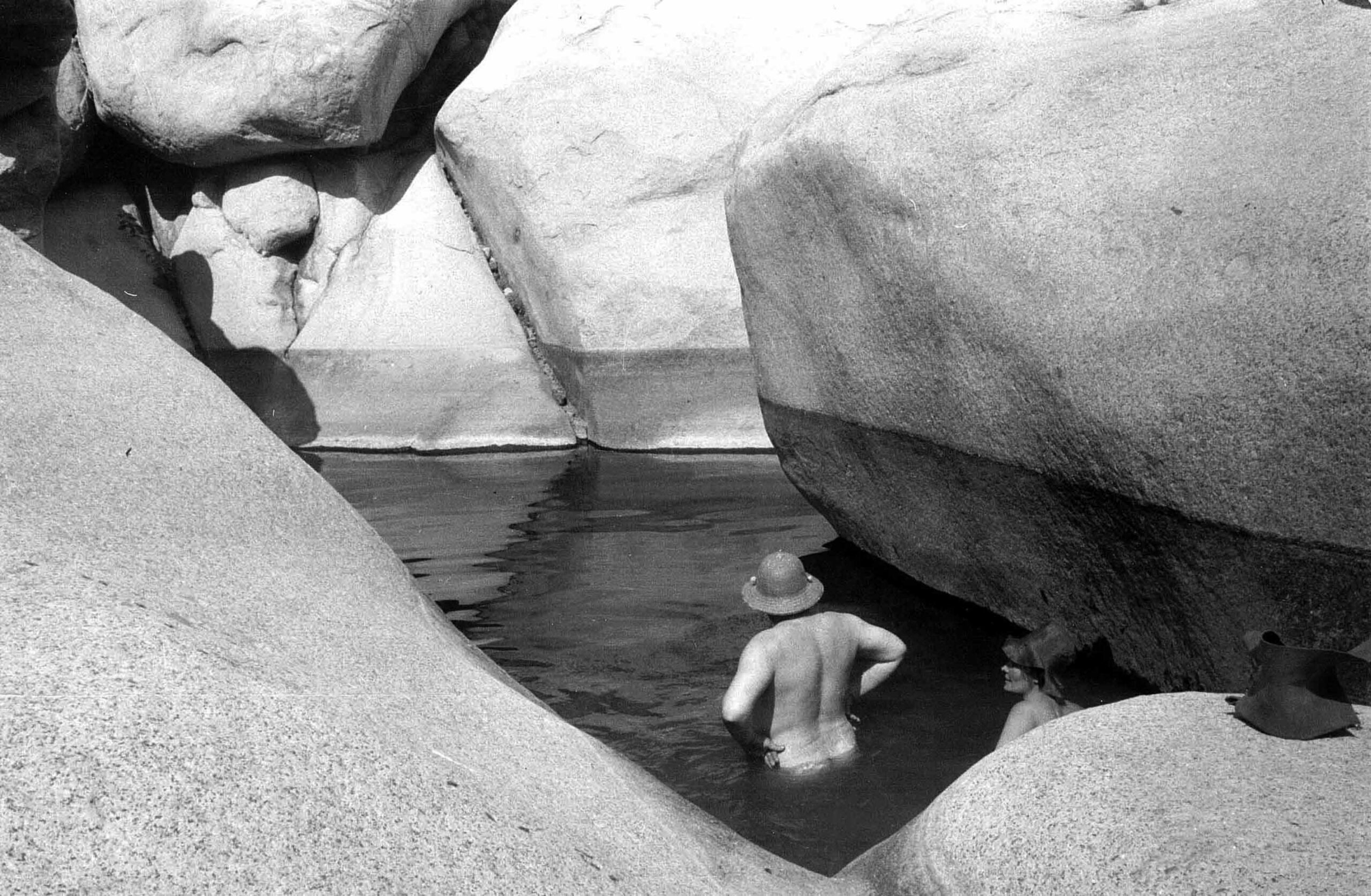

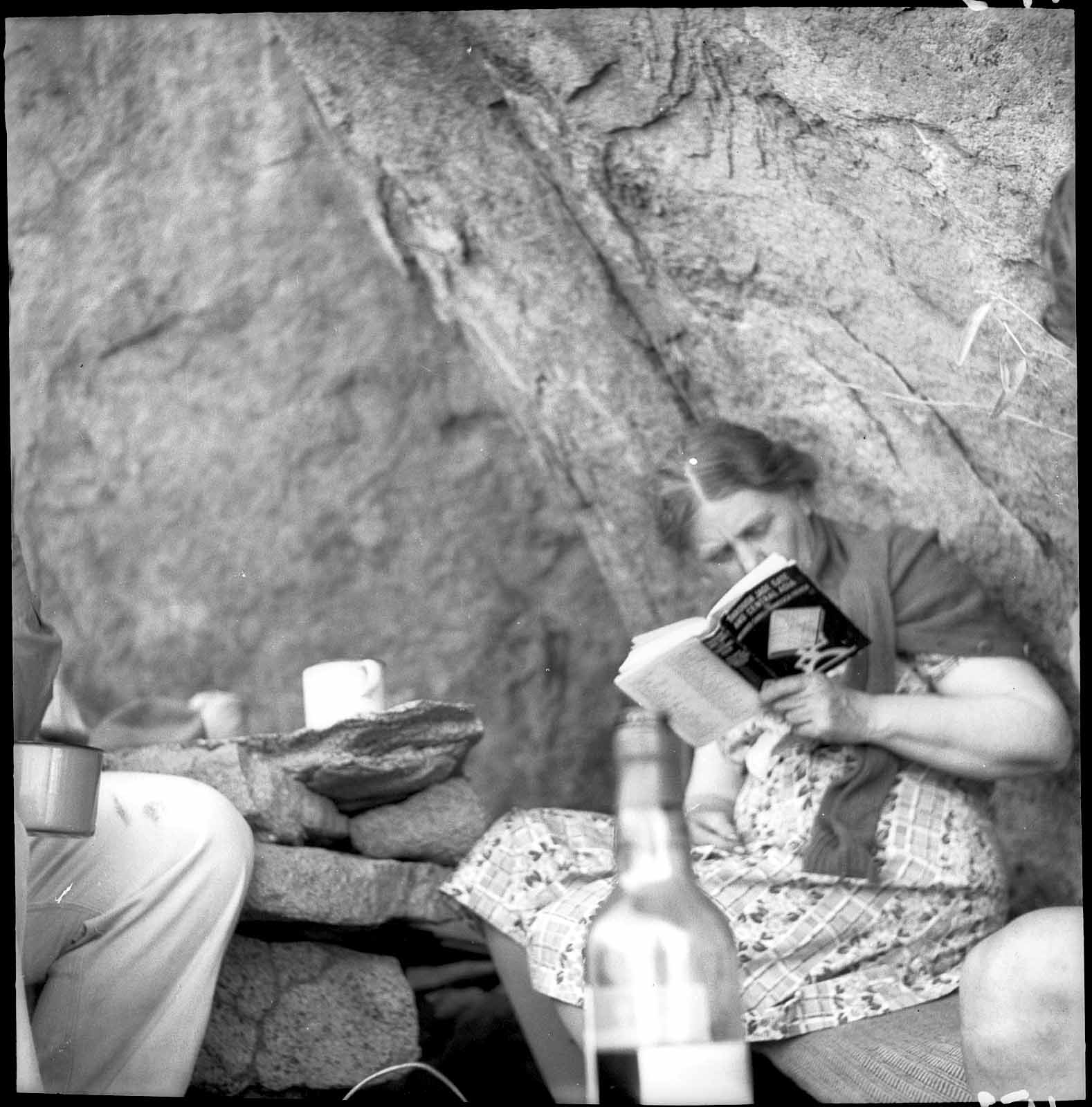

The image archives of the rock art expeditions to the Dâureb and the Erongo reflect excitement among the researchers and reveal re-enactments and visual transformations of what African artists had created centuries earlier in spiritually-infused landscapes. They explore shadow photography, “play the Native”, and celebrate Catholic mass. Anneliese Scherz produced a print of Mary Boyle’s profile “with cactus”, the latter dubbing herself as “Mary the Black Lady”.

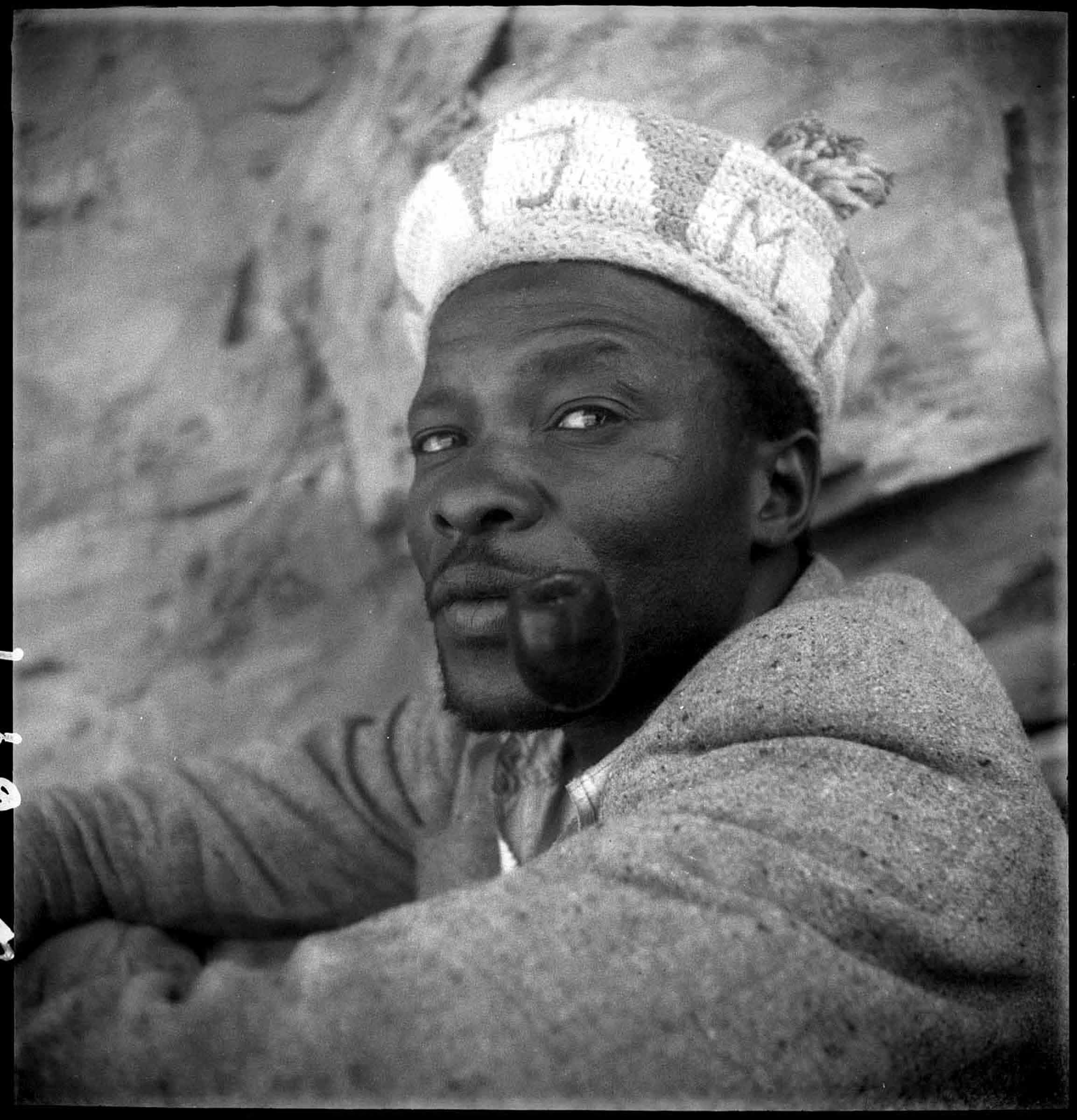

The researchers’ and photographers’ apparent quest for intimacy with the exceptional African landscape produced stark (re-)affirmations of Whiteness. Their attempt to get as close as possible to the rock art reverberates with the apartheid rationales in which colonial research and colonial society at large operated: emptied landscapes devoid of African populations, an African labour economy sustaining the expeditions, technological investments (cars and equipment), and racialised history.

The frieze, and as such “Our Lady” (Boyle) were, as a first consequence of the expeditions, caged behind iron bars and locked gates. The African ancestors of this landscape were literally and otherwise locked out and caged in, as were the expedition’s workers (were they co-workers?) and their knowledge, interpretations, and contributions.

Did they observe some of the reenactments of Whiteness?

Did they flee the scene?

History is full of curiosities and erasures. The present is full of questions. The future, hopefully, provides us with enough time to look for answers.

When we listen closely to history, we hear echoes of lingering violence.

Anneliese Scherz (née Fuss-Hippel, 1900-1985) was a Berlin-trained photographer who settled in Windhoek in 1938 and became well-known as a research expedition photographer. Ernst Rudolf Scherz (1906-1981), a chemical engineer, emigrated to Namibia in 1933, and became the managing director of the Karakul Breeders’ Society and the country’s foremost rock art specialist. The couple’s home in Windhoek formed a centre for emigrants from Nazi-Germany and post-WWII international academics working in Namibia. They relocated to West Germany in 1980.

Curated by Heidi Brunner, Dag Henrichsen, Susanne Hubler Baier, and Lisa Roulet from the Basler Afrika Bibliographien (BAB) Archives Team, based on a BAB and University of Basel student working group exhibition shown in Basel, Windhoek, and Uis, 2016-18. BAB is the largest Namibia documentation centre outside Namibia. Its vast library and archive holdings are mainly used by scholars working on Namibian historical topics with its website providing information ranging from catalogues, books, comics, posters, photographs, and audio-visual recordings from Namibia.